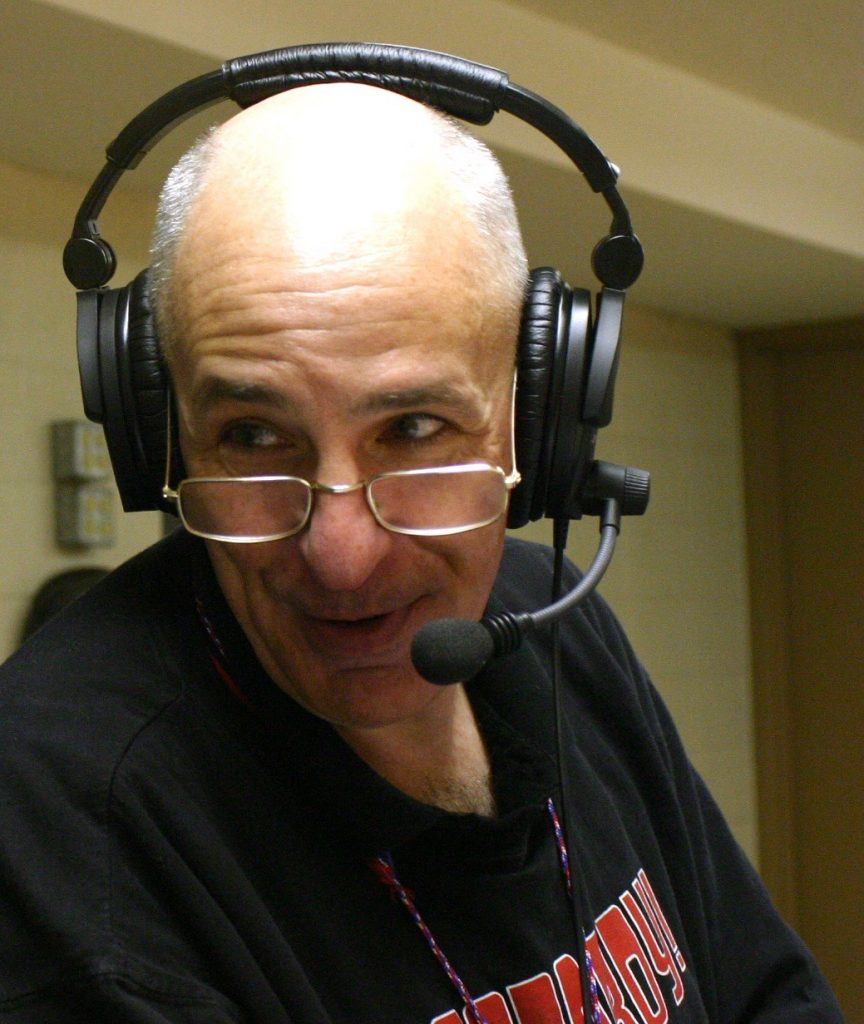

A professor of journalism at Union University in Jackson, Tn., Steve Beverly is a frequent contributor to All On Georgia/Muscogee. Earlier in his career, he was a reporter and anchor at three stations in Columbus, Ga. He publishes a blog for news professionals called The Old TV News Coach. This post presents Beverly’s personal views and do not reflect the opinions of the management or staff of All On Georgia.

Periodically, The Old TV News Coach tackles weaknesses in television news presentation. The object is not merely to be critical or to sound like the old geezer in a rocking chair in front of The New Southern Hotel in Jackson, Tn.

The idea is to see our industry of broadcast journalism improve and become far better than it is. Likewise, I take genuine joy in pointing out quality practices that serve the viewer well and reflect credit on the profession.

In the last week, I have witnessed three first-class efforts in the midst of the two most frightening words of the current day: active shooter.

In the last week, I have witnessed three first-class efforts in the midst of the two most frightening words of the current day: active shooter.

This is not to minimize the efforts of competing stations in these cities but I take my hat off to reporters and anchors at KHOU in Houston, Tex., WMBB in Panama City Fla. and WTHR in Indianapolis, Ind.

The mass shooting at Santa Fe High School in Texas had many of us uttering what is now an angry cliche: “Here we go again.” The loss of eight students and two teachers stirred up the national debate on gun possession, mental illness and overall security measures at American schools.

KHOU was the most accessible Houston-area television station for me on Roku. Shortly after 12 noon on that Friday, I saw one of the most impressive pieces of work to sort out truth from fiction and rumors.

https://media.khou.com/embeds/video/8133320/iframe

Reporter Tiffany Craig, using the equivalent of an electronic chalkboard, set up three columns: one for verified information, one for false reports and a middle section for possible but unsubstantiated data. Craig’s work reminded me of the stories of Walter Cronkite explaining complex stories on WTOP in Washington (prior to his joining CBS News). In the early days of television he employed “chalk talks,” using a blackboard and chalk to detail specific facts in understandable fashion.

Several times during the afternoon Craig performed solid work, especially in diffusing wildfire rumors that erupted on social media. Typically in today’s cyberculture, false information spreads from online users who claim to know people who know people who have so-called specifics that they are sure the media is not reporting.

Craig did not do her work in a lecturing fashion but was almost like watching the best schoolteachers as she turned to her electronic board, illustrated the key points and turned to the camera to talk to viewers in a calm, non-threatening fashion.

The video of Craig’s work we have embedded should be a textbook for every newsroom in America on how to sort truth from baloney for viewers during crisis situations.

Three days later, in Panama City, my old friend and colleague Jerry Brown and his co-anchor and assistant news director Amy Hoyt demonstrated how small market journalists can be just as professional during a crisis.

Before Brown and Hoyt took over, morning and noon anchors Chris Marchand and Kelsey Peck did a first-rate job of guiding viewers in the Florida Panhandle through an active shooter at a local apartment complex.

While Marchand and Peck were at the anchor desk, reporter Megan Myers—who has only been with WMBB a few months—was in the midst of interviewing a neighbor in the area where 49-year-old Kevin Holroyd erupted. As police were attempting to bring an end to the violence, shots rang out behind Myers and the man she was interviewing.

While Marchand and Peck were at the anchor desk, reporter Megan Myers—who has only been with WMBB a few months—was in the midst of interviewing a neighbor in the area where 49-year-old Kevin Holroyd erupted. As police were attempting to bring an end to the violence, shots rang out behind Myers and the man she was interviewing.

http://www.mypanhandle.com/news/shots-fired-while-reporter-is-on-air/1192587128

Despite the fact that the sequence quickly unfolded and went viral on social media, WMBB did a professional job of following the story with marathon coverage while not employing alarming language or sensational tactics.

I’m familiar with the work of Jerry Brown. He was my prime time male anchor when I was news director at WWAY in Wilmington, N.C. Jerry had the vocal delivery and straightforward approach that viewers need in nervous moments. In September 1984, when Hurricane Dora was pounding the Atlantic coast and downtown Wilmington for hours, Jerry and his colleague Stella Shelton were stalwarts all night long and into the early hours of the following day.

When I received an alert of the Panama City eruption, I would have been surprised if Jerry had been anything but what he was — the calming voice to a city which eight years earlier watched as an unstable man fired shots at Bay County school board members.

When I received an alert of the Panama City eruption, I would have been surprised if Jerry had been anything but what he was — the calming voice to a city which eight years earlier watched as an unstable man fired shots at Bay County school board members.

The shooter missed all of his targets but was shot by a security officer multiple times before finishing the job himself.

Jerry’s co-anchor Amy Hoyt was solid at delivering point-by-point retrospectives and summaries of what transpired for latecomers to the story. WMBB did not employ a video chalkboard but Hoyt was adept at outlining the day and the unanswered questions in one-two-three sequences. Jerry and Amy brought viewers up to date within a matter of minutes.

This blogpost is being written approximately 15 hours after violence exploded at Noblesville West Middle School near Indianapolis. At this hour, a teacher who was shot is emerging as a hero of the day, Jason Seaman, is apparently out of danger. A vigil continues for a 13-year-old girl who was shot, apparently by a classmate who asked to be excused from the class and returned with two revolvers.

I stayed with WTHR for better than three hours. In any marathon coverage of a crisis, television news has to draw a fine line between being invasive with parents and, in the case of Noblesville, with students of middle school age. The wrong reporter can quickly turn off viewers either with insensitive questions or giving the impression of not respecting frayed emotions after an active shooter.

One reporter who impressed me specifically was Steve Jefferson. He was sent to Noblesville High School. Emergency personnel made the decision to send the middle school students via a large motorcade of buses to the high school to decompress and reunite with their parents.

Jefferson was especially sensitive with the mother of a 14-year-old for one key reason — he listened. Jefferson did not bombard her with questions. He allowed her to talk and go through the myriad of emotions she was experiencing.

A key moment in that interview was when the mom expressed what virtually every parent had to be feeling in Noblesville: “I don’t want to sound insensitive to say that I’m glad my daughter wasn’t hurt … but I’m glad my daughter wasn’t hurt.”

One of the keys to good interviews in any situation, crisis or feature, is for reporters to be good listeners. Jefferson listened. His followup questions connected with what the woman previously said and advanced the story without heightening hysteria.

A couple of low moments during the three crises: one station made use of the phrase “bring closure.” In the case of the Holroyd story, one reporter said, “Kevin Holroyd is now dead, and this will no doubt bring closure to many people who have been on edge during this long day.”

I wrote in an earlier blogpost (and was backed up by several working producers) that the word “closure” is the most misused in television news today. Victims or people who have been in harm’s way from an active shooter often need weeks, months, or even years, if ever, to experience closure to violent moments. Families of victims who lose their lives do not suddenly find closure if a perpetrator is killed by law enforcement officers or if the shooter takes his (or her) own life.

Three times during the Noblesville coverage, I saw WTHR reporters respond to anchor tosses with “good morning” or “good afternoon.” When one is covering a murder or potential murder, the morning or afternoon definitely is not good.

That becomes an anachronism of habit and often conveys insensitivity. Producers and news directors should drop the “good morning” or “good afternoon” response from live field reporters. Teach reporters to go straight into their narrative, especially at a crime scene.

Still, I was impressed by KHOU, WMBB and WTHR with no intent to minimize the work of their competitors that I did not witness. In Houston, Panama City and Indianapolis, that trio comprise what I sometimes refer to as Allstate stations:

You’re in good hands if you watch them for news.

Chattooga Opinions

Medically Supervised Weight Loss: Inside Premier Weight Loss & Medispa

Chattooga Local News

Georgia Power Files Plan for Customer Rate Decrease with Public Service Commission

Chattooga Local Government

Carr Pushes for Permanent Halt of Medicare and Medicaid Funding for Child Sex-Change Procedures

Bulloch Public Safety

02/20/2026 Booking Report for Bulloch County

Bulloch Public Safety

01/26/2026 Booking Report for Bulloch County

Bulloch Public Safety

02/09/2026 Booking Report for Bulloch County

Bulloch Public Safety

02/16/2026 Booking Report for Bulloch County

Bulloch Public Safety

02/02/2026 Booking Report for Bulloch County

Bulloch Public Safety

01/30/2026 Booking Report for Bulloch County