Summerville Fire Chief Robbie Lathem recently was featured in the Cherokee Phoenix, the oldest Native American newspaper in the United States. The paper has been published since 1828, and was the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States and the first published in a Native American language.

In January 2007, the newspaper launched a website and began publishing in a broadsheet format. Today, the newspaper reports on the tribe’s government, current events and Cherokee culture, people and history. The news organization has also broadened its outreach to include locally aired radio shows, Facebook posts, Twitter feeds, Instagram profiles and a YouTube channel.

“It was a fun interview and quite honestly an honor to me to have a featured story in the oldest Native American newspaper,” Lathem said.

Lathem, who is a member of the Cherokee Nation, serves as the city of Summerville’s Fire Chief, a position he has held since 2016. He is the city’s sixth fire chief since the department was established in 1936.

Lathem told the Native American paper about his role as fire chief in Chattooga County’s county seat and his interest in family history that involves his Native American roots.

“As a kid I remember my great-grandmother talking about a lot of stuff,” Lathem explained during the interview with the Cherokee Phoenix. “As I got older, my dad’s sister, she was always big with genealogy. She was researching it really before the internet was prevalent. So she worked and worked and worked to try to get her citizenship. Originally she got denied, then she appealed to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and then they reversed it and granted her citizenship.”

Once his great-aunt was granted citizenship to the Cherokee Nation, Lathem began the process for himself.

The article also emphasizes Summerville’s proximity to the former Cherokee Nation capital, “Summerville is located 22 miles west of Calhoun, Georgia, once called New Echota, a pivotal site for Cherokees as their capital and also where the Trail of Tears officially began. The Summerville city park features an 8-foot-tall, wooden statue of Cherokee linguist and scholar Sequoyah, who spent 12 years developing a syllabary, or written language, for his people.”

The article on Lathem is titled, “Cherokee helping keep small Georgia city safe”, it was written by Chad Hunter.

Cherokee Nation is comprised of the descendants of Cherokees and Cherokee Freedmen who removed here to Indian Territory (present-day northeastern Oklahoma) in the 1800s, either as “Early Settlers” prior to 1830 or through forced federal relocation commonly known as the “Trail of Tears.” Cherokees who established themselves in this new land were listed on several tribal censuses. A final federal census called the Dawes Rolls was taken of tribal citizens living here from 1898-1906. To be eligible for Cherokee Nation citizenship, a person must have one or more direct ancestors listed on Dawes.

The Dawes Act of February 8, 1887 was a turning point in determining tribal citizenship. The Act developed a Federal commission tasked with creating Final Rolls for the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). The Commission prepared new citizenship rolls for each tribe, incorporating names of approved applicants while simultaneously documenting those who were considered doubtful and ultimately rejected. Upon approval of the Rolls, the Dawes Commission allotted a share of communal land to the approved individual citizens of these Tribes in preparation for Oklahoma statehood (1907). The Dawes Commission required that the individual or family reside in Indian Territory to be considered for approval.

While the official process started with the 1896 Applications, these were eventually declared null and void. Two years later, the Curtis Act amended the process and required applicants to re-apply even if they had filed under the original 1896 process. With new guidelines in place, the Commission continued to accept applications from 1898 through 1907, with a handful accepted in 1914. The list of approved applications created the “Final Rolls of the Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory.” –source www.archives.gov

Lathem is the first to admit the process to be admitted into the Cherokee Nation was challenging, but one he is very thankful his great-aunt tackled.

When it comes to his Cherokee history, Lathem said he tries “to read and figure out as much as I can.” He also attends Cherokee meetings and gatherings.

Lathem with the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr.

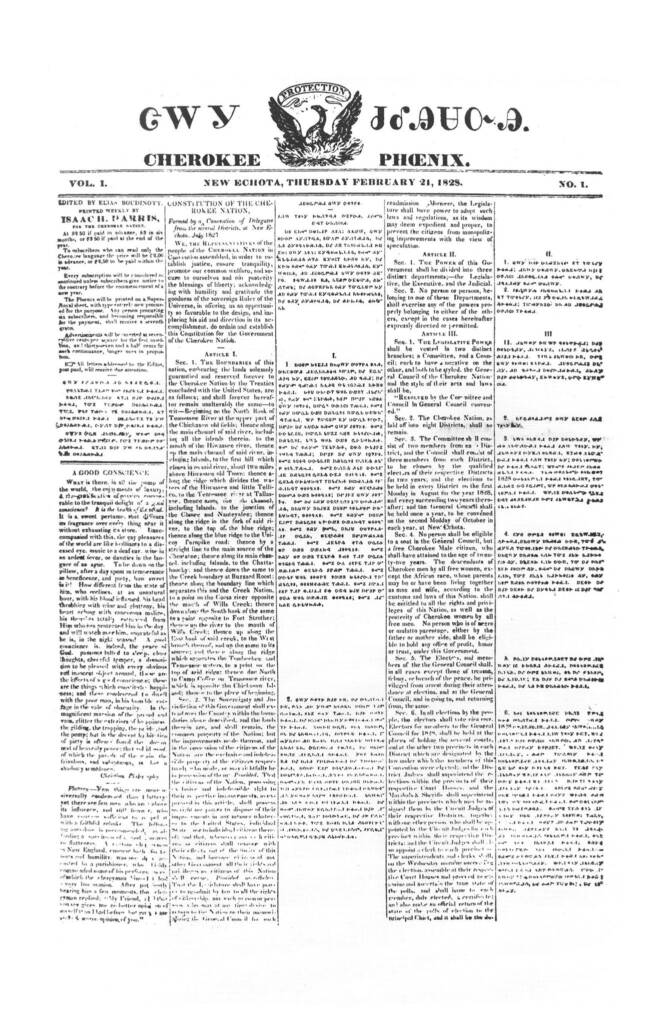

History of the Cherokee Phoenix

The first issue of the newspaper was printed on Feb. 21, 1828, in New Echota, Cherokee Nation (now Georgia), and edited by Elias Boudinot. It was printed in English and Cherokee, using the Cherokee syllabary created by Sequoyah.

Rev. Samuel Worcester and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions helped build the printing office, cast type in the Cherokee syllabary and procure the printer and other equipment. Also, Boudinot, his brother Stand Watie, John Ridge and Elijah Hicks, all leaders in the tribe at that time, raised money to start the newspaper.

In 1829, the newspaper name was amended to include the Indian Advocate at the request of Boudinot. The Cherokee National Council approved of the name change and both the masthead and content were changed to reflect the paper’s broader mission.

In the 1830s Boudinot and Principal Chief John Ross used the Cherokee Phoenix to editorialize against the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the growing encroachment and harassment of settlers in Georgia.

The newspaper also contained news items, features, accounts about Cherokees living in Arkansas and other area tribes, and social and religious activities. The two U.S. Supreme Court decisions (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia), which affected Cherokee rights, were also written about extensively.

As pressure for the Cherokee to leave Georgia increased, Boudinot changed his stance and began to advocate for the removal of Cherokee to the west. At first Chief Ross supported Boudinot’s opposing view but by 1832 the two leaders’ differences caused them to split and Boudinot resigned.

Elijah Hicks, a brother-in-law of Ross, was appointed editor in August 1832, but the Phoenix was silenced in May 1834 when the Cherokee government ran out of money for the paper. Attempts were made to revive the paper. When word leaked that Chief Ross intended to move the printing press from New Echota to nearby Red Clay, Tenn., the Georgia Guard, who were already brutally oppressing the Cherokee people, moved in and destroyed the press and burned the Cherokee Phoenix office with the help of Stand Watie who was a member of the Treaty Party. The party advocated selling what remained of Cherokee land and moving west.

Four years later most of the Cherokees who remained on their lands in Georgia, Tennessee and North Carolina were rounded up and forcibly marched or sent by boat to Indian Territory.

A Cherokee Nation newspaper was again published in September 1844 in the form of the Cherokee Advocate. The paper was published in Tahlequah and edited by Cherokee citizen William Potter Ross, a graduate of Princeton University.

The Cherokee Advocate returned after the Cherokee government was officially reconstituted in 1975. The newspaper continued under that name until October 2000 when the paper began using the name Cherokee Phoenix and Indian Advocate again. Also, that same year, the Tribal Council passed the Cherokee Independent Press Act of 2000, which ensures the coverage of tribal government and news of the Cherokee Nation is free from political control and undue influence.

In January 2007, the newspaper began using the original Cherokee Phoenix name, launched a website and began publishing in a broadsheet format. Today, the newspaper reports on the tribe’s government, current events and Cherokee culture, people and history. The news organization has also broadened its outreach to include locally aired radio shows, Facebook posts, Twitter feeds, Instagram profiles and a YouTube channel.